This is the view when landing at the highest point accessible by airplane, the village of Lukla. The closest road is a week’s hike down to the lower elevations; we headed in the opposite direction up into the Himalayas. The gravel airstrip here angles into the side of the mountain, which actually aids the airplanes: upon landing, the uphill stretch helps slow the plane before running into the two houses at the end of the airstrip; upon departing, the pilots position the plane at the top of the airstrip, apply the brakes, rev their props up to full speed, and let go of the brakes to get a quick full revolution boost down the bumpy runway before lifting off just as the airstrip drops off the end of a cliff. We set up our local air travel and porter arrangements with an excellent contact in Kathmandu who arranges treks and other travel needs in the area. If you ever plan to go to Nepal, I highly recommend contacting Karki at Naso Reisen. He’s very knowledgeable, helpful, dependable, and also a very nice guy.

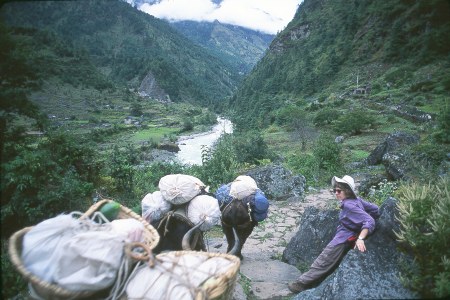

Karen practicing her dzopkyo avoidance stance, on the way up valley. Dzopkyo are infertile male crossbreeds between yak (which are much hairier and only live in the higher elevations) and cows; they are used to move goods along the trails. Human labor is so inexpensive here, though, that porters outnumber pack animals by a huge margin. Plus, porters frequently carry 120 pounds each, with larger porters carrying up to 200 pounds! All while wearing flip-flops or even no shoes, moving up steep mountain trails, with the weight suspended in wicker baskets by straps across their foreheads, and with smiles on their faces! The next time you complain on a backpacking trip about anything, think about Nepali porters for a dose of reality.

Our nice porter Kamal resting as we descend into Sagarmatha National Park (“Sagarmatha” is the Nepali name for Everest). He carried both of our backpacks, lashed together, at the same time. He actually considered it a light load, compared to what he usually carries for large expeditions, and we’re apparently much more lucrative. I thought that Washington and Oregon had a lot of waterfalls, at least until heading up valley along the Dudh Kosi (Milk River)! The area is very green and lush, in sharp contrast to the barren windswept areas at the higher elevations.

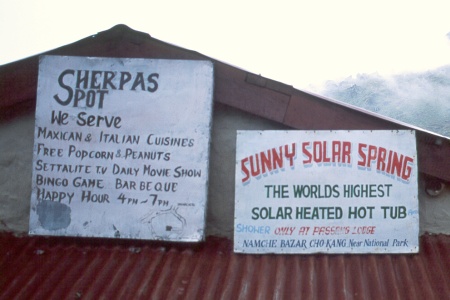

Looking down into Namche (a.k.a. Namche Bazar). This is the only area in the entire Solu Khumbu region that has electricity (because of a small hydroelectric dam project put in by a European group). Unlike the rest of our trek, here we had warm showers, a light bulb in our room, and listened to jukeboxes and TVs hooked up to VCRs. The week before we arrived, some porters had hauled up brand new Pentium III computers and monitors for a resourceful lodge owner who charged expensive rates to allow wealthy Westerners to access the Internet via satellite phone. Electricity has completely changed the dynamic, ambiance, and culture of this large village.

Meat being hacked up with a dirty machete on some cardboard in the mud at Namche, and then weighed on a rusty metal balance scale. Animals would be slaughtered at lower elevations and brought up in the porters’ wicker baskets, open to the sun and insects, getting progressively more “aromatic and flavorful” as they went. After a couple days of selling pieces along the way to families and lodge owners, they would sell the rest at Namche. We avoided meats and dairy products on the trip for health reasons, and I still got very sick on several occasions from the food. No wonder why…

You have to give this enterprising Sherpa credit for finding all the little tricks that he could glean from his Western visitors. Give ’em what they want… all of it!

Cloud-shrouded chorten (Tibetan stupa) at Mong La. The prayer flags send Buddhist prayers on the winds around the world. After crossing this pass in the mountains, we descended on a mucky trail through woods. When we came over this pass on our return, we stayed at the lodge that is barely visible in the fog on the left, and had a nice evening with a British/Dutch couple who also stopped there for the night.

A Buddhist stupa and mani wall (which contains Buddhist mantras carved into the flat rocks) at the pass between Syangboche and Khumjung. It is considered virtuous and appropriate to walk along a mani wall by keeping it to your right, just as you should walk around a stupa clockwise.

Karen showing off the Ritz Carlton at Phortse Tenga. We decided to go for the super expensive option: 30 cents a night to stay there. The only other lodge was 15 cents, but it’s smoky kitchen was in the sleeping room, and this one had a rock wall separating the rooms. This is a classic dormitory style lodge that can be found along the trails, open during some parts of the year. The plywood beds are covered by thin, damp, dirt-stained foam pads; the floors are made of dirt covered by flat rocks, and the tarps on the walls help keep out drafts between the cracks in the rock walls. Some lodges had a single fluorescent light bulb powered by a solar charged battery; the one in this picture didn’t work, though. The toilet is a hole in the floor of a rock outhouse. All fairly basic, but our sleeping bags were comfortable and it sure beat setting up camp every night, plus we got to meet some really neat local people and travelers from around the world in these lodges.